Building Up to OpenStack — QEMU and Your Cloud

Republished from https://www.ibm.com/blogs/bluemix/2016/10/building-up-to-openstack/

Recently, in the midst of a cloud customer support crisis, a new, young engineer asked a more senior engineer, “Quick…what is QEMU and how do I restart it?” That question has led to the creation of this article. It’s time to take a deeper look into the very nucleus of an OpenStack cloud—it is QEMU (Quick Emulator)!

As we see how QEMU is connected to all the other functional parts of a cloud, we will build up our general understanding of OpenStack, from the core to the very top, from the essential running instance to the Horizon dashboard that the user sees. If you’re not yet familiar with IBM Bluemix Private Cloud and OpenStack, you can check out this article to get a brief introduction.

OpenStack adoption increases with each release cycle, and with good reason: it addresses a variety of common use cases and consumption models. Still, developers can find it difficult to appreciate OpenStack, or indeed to understand it fully, with its incomplete features and the increasingly complex interrelationships among its parts. Therefore, it’s good to avoid making assumptions about what our co-developers know about the fast-moving target that is OpenStack.

QEMU: open source machine emulator and virtualizer

QEMU, short for Quick Emulator, began its existence as an unremarkable software emulator for a variety of CPU architectures. It was also useful for testing various CPU architectures, such as ARM or SPARC. Initially, QEMU offered limited I/O options: files for block devices (disks) and tap(3) interfaces for network devices.

When it comes to the cloud, it’s important to understand that all memory allocated to a running virtual machine (VM) is used by the QEMU process. This is true in the case of pure QEMU and QEMU + KVM cases, which we are discussing here. For this reason, in many ways, QEMU actually IS the running instance of the VM. In other words, if you merely connect the QEMU process to a storage device and a network, you have created an atomic cloud, a fundamental machine:

Atomic QEMU = a fundamental machine emulator

Let the race toward OpenStack’s complexity begin! However, speaking of races, QEMU itself is not as fast as most people would like it to be. In its pure state, QEMU translates and validates the memory ranges of each instruction, and interprets each one. All instructions must be emulated.

Atomic QEMU + KVM = better performance

Kernel Virtual Machine (KVM) adds high-performance CPU and memory virtualization to our atomic cloud by utilizing new CPU instructions; it’s a fast path for the most frequently invoked CPU instructions and for memory access. KVM now supports x86, IBM POWER, and ARM.

KVM turns QEMU into its helper, because KVM handles regular instructions faster. However, certain privileged instructions can cause QEMU + KVM to slow down as it falls back to the interpreted QEMU path.

Generally your VM runs much faster when KVM is allowed to assist QEMU. Until you hit a privileged instruction, execution proceeds natively on the underlying hardware CPU. When a privileged instruction is reached, in a virtual context, that means there is an “up call” and KVM has to ask QEMU what to do with that instruction.

By adding KVM to the picture, you are essentially taking the virtual CPU and memory out of QEMU (for emulation) and using KVM (for configuration) to control execution by the hardware CPU, for reasons of speed.

To summarize, as depicted in the diagram above, think of QEMU as an interpreter, a software evaluation path of CPU instructions––and KVM as a faster execution path for those underlying instructions:

Dissecting the atomic machine: QEMU and storage backends

If you take a look at qemu disk space help, you can see that QEMU actually supports a lot of different storage back ends. If you separate the storage-related activities out of QEMU, there is an entire industry that has developed. Essentially, we have taken everything we learned about virtual memory up until the 1970s and applied that knowledge into storage technology. By using extents of 4MB or so, instead of pages, we now have:

- copy on write

- snapshotting

- thin provisioning

- tiered storage

For example, a modern storage solution such as Ceph RBD (RADOS Block Device) combines the rich storage features above with network accessibility, thus providing optimizations in speed, resiliency, and redundancy while still allowing remote access. As a further optimization on cloud storage solutions, one can remove QEMU entirely from the I/O path to optimize guest-to-I/O performance. We will cover that topic in a subsequent article.

Virtualized servers nearly equal to bare metal server performance

With KVM, QEMU and some storage and network backend technologies such as Ceph RBD, we can achieve CPU, memory, disk and network performance levels that exceed the performance of bare metal servers from a few years ago. They also gain the operational flexibility afforded by newer storage features such as thin provisioning and snapshots. On the hardware available today, these solutions are faster than ever before.

Building up to OpenStack

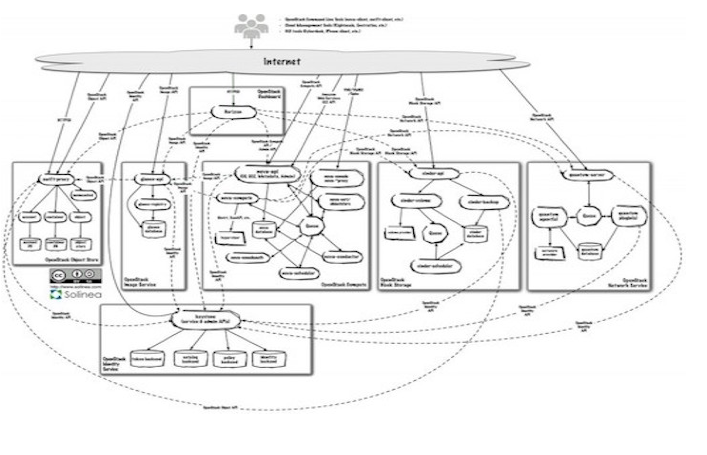

As we are building up to the complexity of OpenStack, an important concept to remember is that the QEMU process assumes there is only a single user. In essence, using an OpenStack VM merely adds the power of multiuser capability, ease of initial VM configuration, and additional security to the atomic VM machine that QEMU fundamentally has instantiated. Eventually, we’ll be looking at an OpenStack “machine” that delivers complexity like this:

OpenStack Grizzly Release — This was a while ago!

Because we know the OpenStack cloud down to its roots, IBM Bluemix Private Cloud can deliver exceptional product performance and service to our customers. Take the time to learn more and stay tuned for upcoming articles as we continue to dive into the basic elements of cloud computing.